Introduction

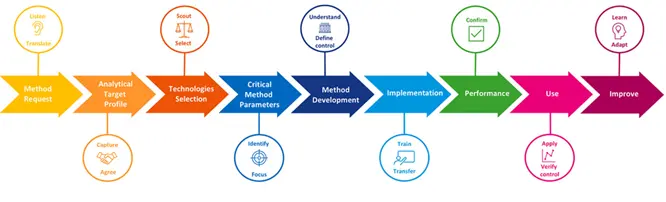

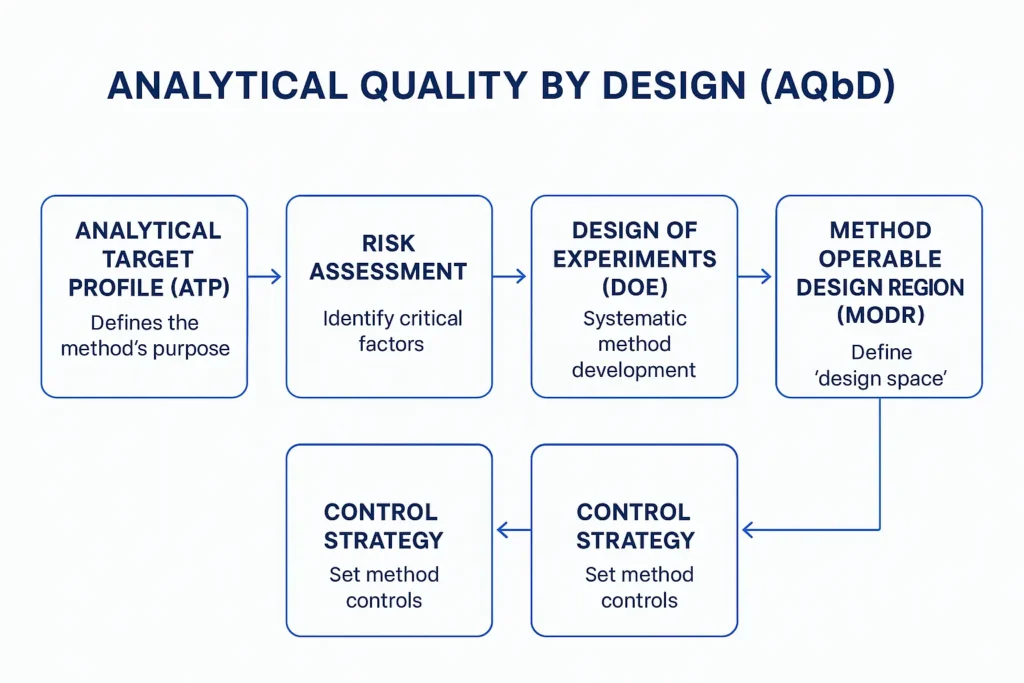

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) represents a paradigm shift in how analytical methods are conceived, developed, validated, and maintained throughout their lifecycle. In Part I of this series, we established the foundations of AQbD, explored its regulatory drivers, and introduced the concept of lifecycle-based analytical control. At the heart of this modern framework lies the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) — the single most critical element that differentiates AQbD from traditional analytical method validation.

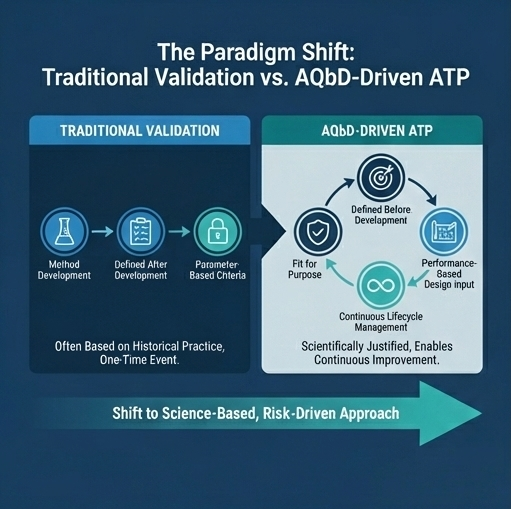

In conventional analytical development, performance characteristics such as accuracy, precision, and linearity are often assessed after the method has already been developed. Acceptance criteria are frequently borrowed from guidelines or historical practices, sometimes with limited scientific justification. In contrast, AQbD requires that analytical performance expectations be defined prospectively, before method development begins. These expectations are formalized in the ATP.

This article focuses entirely on the ATP: what it is, why it matters, how to define it correctly, and how it serves as a contractual link between product quality requirements and analytical method performance. By the end of this article, the reader should be able to confidently design, justify, and defend an ATP in both internal quality systems and regulatory inspections.

Key Takeaways: Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

- The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) defines analytical performance requirements before method development.

- ATP is the cornerstone of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and lifecycle-based control.

- ICH Q14 formally establishes ATP as a regulatory expectation.

- ATP links product Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) to analytical method capability.

- If an analytical procedure meets the ATP, it is fit for its intended purpose—regardless of method changes.

Regulatory Context and Evolution of the ATP Concept

The concept of defining analytical objectives upfront did not emerge in isolation. It is the result of a gradual evolution in regulatory thinking toward science-based, risk-driven pharmaceutical development.

2.1. ICH Q14: Analytical Procedure Development

ICH Q14 formally introduces the ATP as a core element of analytical procedure development. It defines the ATP as:

“A prospective summary of the quality characteristics that an analytical procedure should possess to ensure the intended quality of measurement.”

This definition is intentionally broad, allowing flexibility while placing responsibility on the applicant to define what “fitness for purpose” truly means for each analytical procedure.

2.2. Alignment with ICH Q2(R2)

The revised ICH Q2(R2) guideline complements Q14 by modernizing method validation concepts and aligning them with lifecycle principles. Under this framework, validation parameters are no longer evaluated in isolation; instead, they are assessed against the predefined ATP. In essence:

- ATP defines what is required

- Q2(R2) defines how performance is demonstrated

2.3. USP <1220> and Lifecycle Thinking

USP <1220> further operationalizes the ATP concept by embedding it into a three-stage lifecycle:

- Analytical Procedure Design

- Analytical Procedure Performance Qualification

- Continued Performance Verification

Across all three stages, the ATP acts as the reference point for suitability, control, and improvement.

What Is an Analytical Target Profile?

At its core, the ATP is a performance-based statement. It does not prescribe how an analytical method should be executed; instead, it specifies the level of performance the method must consistently achieve.

A well-defined ATP answers three fundamental questions:

- What is being measured?

- Why is it being measured?

- How well must it be measured to ensure product quality and patient safety?

This performance-based philosophy is what enables flexibility in method development, robustness studies, and future improvements without compromising regulatory compliance.

ATP vs. Traditional Validation Acceptance Criteria

One of the most common misunderstandings in AQbD implementation is the assumption that the ATP is simply a rebranding of validation acceptance criteria. This is incorrect.

| Aspect | Traditional Validation | AQbD-Driven ATP |

| Timing | Defined after method development | Defined before method development |

| Nature | Parameter-based | Performance-based |

| Flexibility | Limited | High (within MODR) |

| Scientific Rationale | Often implicit | Explicit and documented |

| Lifecycle Use | One-time | Continuous |

Core Components of a Robust ATP

A scientifically sound ATP is structured, clear, and justified. While the exact format may vary between organizations, robust ATPs consistently include the following elements.

5.1 Analytical Purpose

The analytical purpose defines the intended use of the method. This must be unambiguous and singular.

Examples include:

- Quantitative assay of API in drug substance

- Determination of related substances in a drug product

- Residual active determination in cleaning validation samples

- Stability-indicating assay for shelf-life assignment

Important principle: One analytical procedure should have one primary purpose and one ATP. Combining multiple unrelated purposes under a single ATP is a common regulatory deficiency.

5.2 Measurand and Reportable Result.

The ATP must clearly define what is being reported:

- % label claim

- % w/w impurity

- ppm or µg/mL concentration

- Total vs. individual impurities

Ambiguity at this stage can lead to misalignment between development, validation, and routine use.

Scientific Justification of ATP Criteria

Regulatory agencies increasingly expect ATP criteria to be scientifically justified, not arbitrarily selected.

6.1 Linking ATP to CQAs

ATP requirements should be traceable to Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of the product. For example:

- Tight assay accuracy may be required for narrow therapeutic index drugs

- Low LOQ is justified for genotoxic impurities

6.2 Safety and Clinical Considerations

For impurity methods, ATP sensitivity is often driven by:

- ICH Q3A/B qualification thresholds

- ICH M7 TTC concepts

- Clinical exposure limits

6.3 Process and Manufacturing Capability

Analytical expectations must also consider realistic manufacturing variability. Overly tight ATP criteria can result in methods that are theoretically sound but operationally fragile.

Example ATPs (Practical Illustrations)

7.1 Assay Method ATP Example

ATP Statement:

The analytical procedure shall quantitatively determine the active pharmaceutical ingredient in the drug product over a range of 80–120% of the label claim with accuracy within ±2.0% and precision not exceeding 2.0% RSD, while demonstrating specificity against excipients and degradation products.

7.2 Related Substances Method ATP Example

The analytical procedure shall quantify specified and unspecified impurities at or above the reporting threshold of 0.05%, with an LOQ not greater than 0.05%, accuracy within ±15% at the LOQ, and precision not exceeding 10% RSD.

ATP and Method Development Strategy

Once defined, the ATP becomes the design input for method development. All subsequent activities must demonstrate that the method can meet ATP requirements under realistic sources of variability.

This includes:

- Selection of analytical technique

- Screening of method variables

- Robustness and DoE studies

The ATP also defines what success looks like during development.

Case Study: Analytical Target Profile (ATP) in Practice

Stability‑Indicating HPLC Method for Related Substances of Afoxolaner Tablets

Background

Afoxolaner is an isoxazoline antiparasitic active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) widely used in veterinary chewable tablets. During manufacturing and throughout the product lifecycle, Afoxolaner may generate process‑related impurities and degradation products, particularly under stress and long‑term stability conditions. Regulatory agencies, therefore, require a stability‑indicating analytical procedure capable of detecting and quantifying these impurities at low levels.

To ensure a science‑ and risk‑based analytical development strategy aligned with modern regulatory expectations, an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) was established before method development, in accordance with ICH Q8, ICH Q14, USP <1220>, and the Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) framework.

Purpose of the ATP

The ATP defines what the analytical procedure must achieve, independent of the analytical technique or specific chromatographic conditions.

Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

The analytical procedure shall quantitatively determine Afoxolaner‑related impurities in the drug product with suitable accuracy, precision, specificity, and sensitivity across the specified range, while demonstrating stability‑indicating capability under ICH‑recommended stress conditions.

Intended Use of the Analytical Procedure

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Method type | Stability‑indicating HPLC |

| Application | Release and stability testing |

| Test matrix | Afoxolaner chewable tablets |

| Regulatory use | CTD Module 3, routine QC testing |

Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) Addressed

| CQA | Justification |

|---|---|

| Control of impurity levels | Patient and animal safety |

| Separation of degradants | Stability indication |

| Sensitivity at low levels | Compliance with impurity thresholds |

| Method reproducibility | Lifecycle and global transferability |

Analytical Target Profile Definition

- Individual specified and unspecified related substances of Afoxolaner, expressed as % w/w relative to the API.

ATP Performance Requirements

| Performance attribute | ATP requirement | Scientific rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Baseline separation of Afoxolaner from all known impurities and degradants | Ensures stability‑indicating capability |

| Resolution (Rs) | ≥ 1.5 between critical peak pairs | Accurate quantitation |

| Accuracy | 80–120% recovery from LOQ to 150% of specification | Regulatory acceptance for impurities |

| Precision | ≤ 10% RSD at LOQ; ≤ 5% RSD at specification level | Reliable low‑level control |

| Linearity | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.99 | Quantitative performance |

| Limit of quantitation (LOQ) | ≤ 0.05% w/w relative to API | Safety and compliance margin |

| Analytical range | LOQ to 150% of impurity limit | Trend and stability assessment |

| Robustness | No significant impact from deliberate small variations | Suitability for routine QC |

Regulatory Alignment

| Guideline | ATP contribution |

|---|---|

| ICH Q8 | Defines analytical objectives upfront |

| ICH Q14 | Enables ATP‑driven method development |

| ICH Q2(R2) | Links validation directly to ATP requirements |

| USP <1220> | Supports lifecycle management |

| EMA / FDA | Risk‑based impurity control strategy |

Linking the ATP to Method Development

The ATP guided key method design decisions, ensuring that development efforts remained focused on fitness‑for‑purpose rather than trial‑and‑error optimization.

| ATP element | Method design control |

|---|---|

| Resolution ≥ 1.5 | Selection of C18 stationary phase and gradient optimization |

| LOQ ≤ 0.05% | Detector wavelength and injection volume optimization |

| Specificity | Comprehensive forced degradation studies |

| Precision ≤ 5% | System suitability and injection repeatability controls |

Example System Suitability Criteria (Derived from the ATP)

| Parameter | Acceptance criterion |

|---|---|

| Resolution (critical pair) | ≥ 1.5 |

| Tailing factor | ≤ 2.0 |

| %RSD (six injections) | ≤ 5.0% |

| Signal‑to‑noise at LOQ | ≥ 10 |

Lifecycle Management Perspective

A key advantage of the ATP approach is that the ATP remains constant throughout the method lifecycle, while chromatographic parameters (e.g., column brand, instrument platform) may evolve. Any post‑approval change is justified by demonstrating continued compliance with the ATP rather than re‑establishing historical method conditions.

Key Takeaway

This case study demonstrates how the Analytical Target Profile functions as the cornerstone of modern analytical development, ensuring regulatory alignment, method robustness, and long‑term lifecycle flexibility.

If the analytical procedure meets the ATP, it is fit for its intended purpose.

Conclusion

One of the most powerful aspects of the ATP is its role across the analytical lifecycle:

- Guides robustness and MODR definition

- Supports post-approval changes

- Enables continuous improvement

- Forms the basis of continued performance verification

Changes to the method can be evaluated against the ATP to determine regulatory impact.

Reference

- International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). ICH Q14: Analytical Procedure Development. ICH Harmonised Guideline, Step 4.

- International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). ICH Q2(R2): Validation of Analytical Procedures. ICH Harmonised Guideline.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP). General Chapter <1220>: Analytical Procedure Lifecycle.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP). General Chapter <1225>: Validation of Compendial Procedures.

- FDA. Pharmaceutical Quality for the 21st Century: A Risk-Based Approach. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- EMA. Guideline on the Use of Quality by Design in Pharmaceutical Development.

- Montgomery, D. C. Design and Analysis of Experiments. Wiley.

- Blessy, M. et al. Development of Forced Degradation and Stability Indicating Studies of Drugs. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis.

- Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S). Aide-Memoire on Inspection of Pharmaceutical Quality Control Laboratories.

- PharmaCores. Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD): Foundation.